As an academic, researcher and now crusader on the topic of ‘imposter syndrome’ (particularly among women) it’s my job to keep on top of the current thinking in the scientific community. I also spend a good part of time working on my topic of interest and correcting the myths, fallacies and downright untruths associated with the irrational feeling of being a fake, phoney or a fraud.

For those working as mentors (formal or informal or as supervisors) in the higher education space, it’s important too. The phenomenon has been widely researched in university students and it’s known to be experienced by those who perceive a point of difference about themselves in relation to those around them. People from minority groups (cultural background, gender etc) are particularly prone to feeling less worthy, capable or intellectually able than those around them, despite evidence to the contrary. Those from low socio-economic backgrounds and those who are first in their families to go to university may experience a sense of ‘not being good enough’ in comparison to their peers even though they may be just as, if not more, capable of success at university.

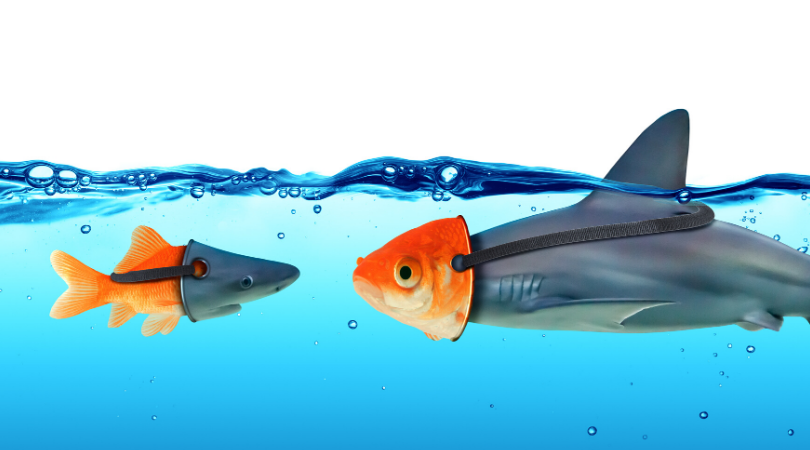

Much of what is termed ‘imposter syndrome’ is not actually ‘imposter syndrome’

You don’t need to be an expert to realise that coming into an unfamiliar community surrounded by people who are thought to be ‘better’ can seriously diminish confidence, reduces incentives to engage in academic and social activities and in the worst case scenario, can lead to perfectly capable people leaving university to avoid the anxiety and stress of it all.

This is serious stuff. And it’s why mentors should get to grips with what this thing really is and what the consequences might be.

Stories about the impostor ‘syndrome’ appear a good deal in popular press and on social media platforms in particular. There’s even TED talks about it. However, much of what is termed ‘imposter syndrome’ is not actually ‘imposter syndrome’ and for mentors who may encounter the term when engaging with new entrants to the uni community, it’s important to be able to separate out the fact from the fallacy.

So here goes.

Firstly. It’s not a syndrome. Please don’t call it a ‘syndrome’ because it’s not one. (I swear I’m going to put ‘IT’S NOT A SYNDROME’ on a T-shirt to make the point.) When PR Clance and Suzanne Imes made public their seminal research they called it the ‘impostor phenomenon’ (IP) for a reason. Granted, syndrome is much easier to say, but what we’re talking about here is more accurately identified as a complex experience that is often contextual and developed over time via social learning. Defined as an internal experience of intellectual phoniness despite success, it can be debilitating and last a lifetime if not addressed.

It’s not something you have or don’t have – it exists on a continuum

Secondly, it’s not something you have or you don’t. It exists on a continuum which means a person could experience IP only occasionally in some circumstances and not at all in others. Alternatively, like some people I’ve interviewed as part of my research, individuals may constantly experience an irrational but very real feeling of being on the cusp of being found out as a faker on the brink of monumental failure. This is stressful and can lead to anxiety, depression and disengagement from university life.

One outwardly successful and capable woman I interviewed said that every morning she sat in her car mentally rebuilding herself just to go into the office. She was absolutely convinced she was unqualified to be doing her job. She did this Every. Single. Day.

So, IP experiences can be few, moderate, frequent or intense. (You can even find out your ‘score’ by doing the original test that was devised by Dr Clance.

Third, this is not simple self-doubt. I see this reported time and time again. “<insert celebrity name here> tells of their battle against imposter syndrome”. Then the story goes on to say that after some soul searching and a bit of confidence building <insert celebrity name here> enjoys success and is now rolling in cash/adoration/Instagram followers/whatever.

It’s not simply self-doubt

This is more likely self-doubt and a normal, often useful experience that can make us better. When faced with something new or challenging, like university assessments or learning activities, we may feel like we’re not equipped. But we do it, succeed, we get over the self-doubt and move on. When something similar happens we can look in our mental ‘rear view mirror’ and take comfort that we did it before and we can do it again. Happy days.

People experiencing IP do not have that ‘rear view mirror’. It might be foggy or broken or missing entirely and this means that they genuinely do not recognise their past achievements or successes. Instead, success or overcoming challenge is seen as luck or attributable to something or someone else and at some point they’re going to get found out for it.

Finally, it’s cyclical. My interviewees told me variants of a similar story. For example, they’d go through similar feelings of dread when something new, like a new module or assessment, came along. They’d procrastinate and self-handicap by putting things off or not asking questions for fear of being found out as a faker. Then they’d be struck by a need to make sure it was perfect, going above and beyond by overworking and frantically trying to polish and polish and polish it until it needed to be handed in or assessed.

Once their work had been handed in, they’d catastrophise about how bad it was and what mistakes they’d made. More often than not, when good feedback or a good mark is received, they genuinely dismiss it as luck, a mistake, the work of others or just doing the job. Rinse and repeat. Rinse and repeat.

This cycle goes on and on. And the tragic thing is, my very own university experience and my interviewees tell me that they know this is happening but they simply can’t stop it. The thoughts, behaviours, the fear continue on time and time again. For some people, they’ll get off the treadmill and quit university altogether. Alternatively, some will live with this and develop stress, anxiety or depression related disorders. Just think of how a life at university could be impacted by this…

Mentoring is one of the best ways to help people to recognise their situation

As mentors, you have the opportunity to recognise this in your interactions with mentees. Indeed, mentoring is one of the best ways of helping people to recognise their situation and then take steps to resolve their view of their own capacities.

Mentoring can help people avoid wasting talent and diminish the real and profound sense of frustration, sometimes crushing fear of failure, fear of success and mental anguish. It is this that is not reflected in quick and dirty media posts that frame this thing up as something that’s easy to get over.

Instead, bright and breezy suggestions such as writing down your achievements and thinking happy thoughts are suggested and they’re all well and good but they don’t recognise that this can be a deeply embedded learned experience. It can, and often does, require a more nuanced and concerted approach. Mentoring is key to helping people do their best work and be comfortable with their achievements. Social media makes light of how easy it should be to get rid of and that only makes matters worse.

Being a mentor is important and it can help others to distinguish fact from fiction in order to better understand why it’s so hard to shift often deeply held but erroneous beliefs about the self that drive these experiences.

In the next post, we’ll talk more specifically about how you as a mentor, can work with others to bring their best and brightest selves to university and to enjoy rather than dread the experience.

Until then, remember folks, ‘IT’S NOT A SYNDROME!!’

Dr Terri Simpkin is an Associate Professor (Teaching) at the University of Nottingham. She is an academic, researcher, consultant, Duran Duran obsessive and self-identified ‘impostor’. She was recently named in the top 50 most influential women in the data economy. Her research into the impostor phenomenon builds on over forty years of investigation and has led to the development of Braver Stronger Smarter – an interlocking suite of programs that help people get to grips with their IP and recognise their true potential without fear.

She is also the founder of @ForFakeSake, a community of people who secretly know they can take on the world if only they could stop their impostor experiences.